They are among the most widespread and best preserved vestiges wherever the domination of Rome reached.

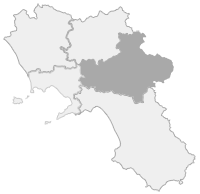

These are the aqueducts, built with techniques that have defied the wear and tear of time. And among the many aqueducts built by the Romans, the longest and most complex crosses half of Campania, from the Apennines to the sea. It is the Augustan Aqueduct, called Aqua Augusta Campaniae, which starts from Serino, among the Picentini Mountains, and reaches the Phlegraean coast, in the magnificent Piscina Mirabilis, one of the most original and impressive Phlegraean monuments. Over 92 kilometers in length along the main route, which, with the addition of the numerous branches, reaches 145 kilometers of the entire circuit.

It was during the empire of Augustus, between 33 and 12 BC, that the large infrastructure necessary to bring water to most of the coastal cities of Campania, including Naples, was built. It was fed by the Fontis Augustei, approximately 376 meters above sea level, close to Mount Terminio, therefore in the Serino area, known for being particularly rich in water. The realization of such a large and complex work arose from the need to ensure the water supply to the increasingly important settlements of the Phlegraean area and, in particular, to the military port of Miseno, landing place of the Classis Misenensis, the great Tyrrhenian fleet commissioned precisely by the emperor Augustus. He assigned the task of designing the new aqueduct to the man most faithful to him, who was also the best engineer Rome had at its disposal in that period: Marco Vipsanio Agrippa, who was curator aquarum at the time.

In its long journey, the aqueduct crosses valleys, overcomes mountains and hills and proceeds for long stretches even underground, in tunnels dug into the rock. The styles used are also different, depending on the geological characteristics of the different areas and the underground or above ground parts.

The route began with two branches running in different directions to reach the intended destinations. A first stretch, which collected water from the "Urciuoli" spring, at 320 meters above sea level, still in the Serino area, ran alongside the Sabato river, reaching Benevento near the Rocca dei Rettori, passing through Prata di Principato Ultra, Altavilla Irpina and Ceppaloni.

The main branch, connected to the higher springs of "Aquaro" and "Pelosi", passes through the territories of Mercato San Severino, Castel San Giorgio, up to Sarno, and then reaches the Nolan plain near Palma Campania, where they are still visible in various sites the remains of the ancient structure. From Palma a branch, built in a second phase in 27 BC, brought the water to the castellum aquae near Porta Vesuvius, from which it was fed into the water network of the city of Pompeii, which was constantly expanding at the time.

The main branch continued through the territories of San Gennaro Vesuviano, Piazzolla, Nola, Saviano, Santa Maria del Pozzo, with long underground sections, to re-emerge in Pomigliano and then in succession Casalnuovo, Afragola, San Pietro a Patierno and San Giuliano, in the locality Red Bridges. Back underground in Sant'Eframo, Santa Maria delle Vegini and Sant'Agnello. There it divided into two branches: the first towards Naples, where it entered from the Gate of Constantinople; the second, longer, completed the route to the Phlegraean area, skirting the base of Castel Sant'Elmo to reach Agnano, Pozzuoli and then Miseno, where it brought the water into the gigantic Piscina Mirabilis. Along the entire route there were, in the end, ten branches to supply, in addition to Naples, Nola, Atella, Acerra, Ercolano, Pompeii, Pausylipon, Nisida, Baia, Pozzuoli, Cuma and Miseno.

The aqueduct and the vast connected water network required various maintenance interventions over time. In particular, the most challenging was carried out in the 4th century, when Constantine was emperor. He personally financed the venture. The consolidation and restoration works of that period were identified later, since they were distinguished by the use of the opus latericium, while the original structure was characterized by the opus reticulatum. There were no shortage of periods of inactivity, even in late Roman times, but in fact the aqueduct remained functional until Charles I of Anjou, when it fell into disuse due to the terrible state it was in.

It was decided to recover it in 1560, on the initiative of the viceroy Don Pedro de Toledo, who commissioned the architect Pier Antonio Lettieri to plan the restoration, but it was never carried out. A second attempt was made three centuries later, in 1860, by the Municipality of Naples, which commissioned it from the architect Felice Abate. Even in that case nothing concrete was achieved, although Abate, after a complete reconnaissance of the route, proceeded to draw up all the plans.

Comments powered by CComment